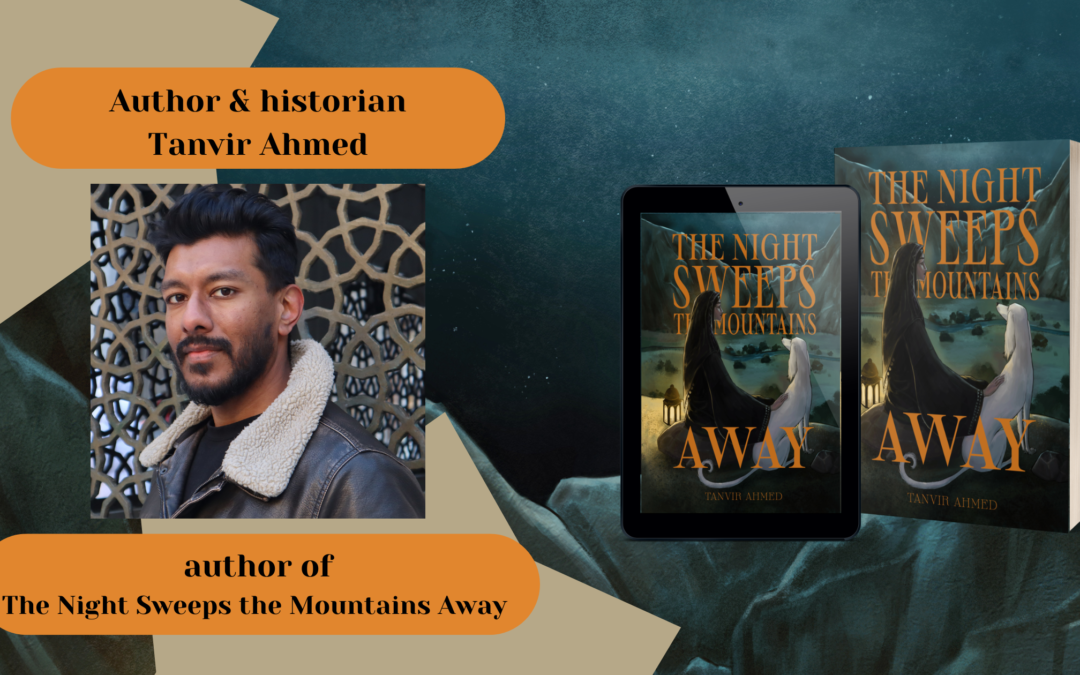

Tanvir Ahmed is a storyteller and historian. His short fiction has appeared in various magazines and collections, including The Year’s Best Fantasy and The Horror Library. He earned his doctorate from Brown University writing on medieval Islamic history, was once a competitive fencer, and is an avid boxer. He lives in the American Southwest.

Can you tell us a little bit about the book, for those who haven’t read it yet?

The Night Sweeps the Mountains Away is, as they say, the story of my heart. I’ll let two resplendent voices speak to what it is—in the words of Maria Haskins and Bogi Takács, it is a story of two people changed by pain, a story of failed rebellion and exile, a vampire story, a story woven from other stories. I cannot say what it will mean to you; that is for you to say, in the ever-shifting dance between reader and tale. I can tell you that for me it is a love letter, among much else, written with all the violence of love.

What draws you to fantasy as a genre?

My commitment to genre is hollow at best. I operate within genres, of course, insomuch as they are historical phenomena that affect all of us in the modern narrative market. But I spend a great deal of time with unmodern literatures that have no notion of “genre” as we are using it here, which puts some (welcome) tension on my relationship to the idea.

One answer is that I am inclined to protest the conceit of literary realism as some sort of universal norm: the idea that the world ‘really’ operates in the way realist literature presumes, reducing everything outside it to superstition, myth, and fancy. This is a colonial conceit used to strip peoples of history. It is also bunk. Just as we scoff at humoral theory and bibliomancy as scientific scaffolds, so too shall others laugh at our industrial-age silliness from other times and spaces.

As a storyteller and historian, my aim is to fight the nonsense of orientalism in the arena of language wherever I may find it. The way fantasy operates as a genre lets me conjure the forms of other literary landscapes, like that of medieval Persian, the narrative tapestry I know best next to English. Then the task is to let those specters of Persian haunt English, hopefully enough to reforge even a small corner of this language, if ephemerally so.

Also, I adore swordfights, monsters, the lush and worked language of epics, rousing film scores, and I came up with a great deal of Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings and Baldur’s Gate.

You are so thoughtful about language, word choice, and even spelling (of loanwords). Why was it so important to you to include Pashto in this book?

You are very kind. What you will find between these covers are fragments of Pashto lyric anchoring the English prose. In the days when these poems and songs were penned, prose authors would habitually stitch their work with verse, from head to foot. Such verses could work as highly compressed distillations of lengthy prose blocks. The heart of the matter, the verses suggest, can burst forth in just these few lines. What more do you really need to know?

Quite a lot, I would answer, as a committed writer of prose (and I believe the same of the authors of whom I speak). The real story is not about accepting the supremacy of poetry or prose, but the art of threading each with the other; letting the tension between the forms bloom into whatever a tale might mean to you. I was seeking to thread myself into such a manner of storytelling.

In my English, I’ve privileged loanwords as they have commonly entered this tongue. Thus will you find dervishes bringing kilims by caravan, not darweshes bringing gelams by karwan. But the Pashto can run unfettered across the page, with all its archaic spellings and unexplained allusions and shifting letters. It is the breath of another language’s universe brushing against my writing. (It is other things to me too, but this is enough for now).

This is sentiment and also argument—I am thinking about the work of Minae Mizumura, or the recent dialogue between J. M. Coetzee and Mariana Dimópulos.

How much were you thinking of present day versus historical upheavals as you wrote this story?

I was not trying to think about any of it per se, but the evil empires do creep in. It’s what the bastards do.

What parts of this story feel most personal to you?

Every last word.

Your writing, both this book and your short stories, is so interwoven with older oral storytelling traditions. What are some stories that have felt formative to who you are as a writer?

I have had many formations, and hope for new ones till I am mixed with the dust. My parents raised me through a garden of books and tales alike; they are the backbone of my writing. A treasure chest of stories comes through the figure of my grandfather, born into an itinerant Pashtun family in northern India during colonial times. The way of being in the world and time conjured by those stories freely dispenses with the colonial and national borders so precious to the oligarchs. It was through Shahzad Bashir’s guidance that I learned how to go diving in the sea of Persian hagiography, history, and letters. Through years of training with him, I learned to better knot my many worlds of story into my love of English prose.

Was there a particular moment or scene in this book that was the seed for this story?

I met Mina many years ago in a dream. I didn’t know who she was, and needed to find out.

Do you listen to music or have other background noise as you write, or do you prefer to write in the quiet?

I always write with music, and I do not repeat music between works. Sometimes I’ll use ambient playlists. I drafted some of The Night Sweeps the Mountains Away to a mix of quieter instrumental pieces from the soundtrack for the movie Tenet, well before I ever saw it, so I associate those pieces more with my book than with the film itself. Sometimes it is the opposite, when I’ll throw a pop song on loop and run it through the night while writing freely. One of those for this book was “Left Right” from Ali Sethi, Abdullah Siddiqui, Maanu, and Shae Gill. The most tightly wound form of all this is where it’s one song for one scene: I ran draft after ragged draft of one sequence to Santa Esmeralda’s “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.”

How much specific research did you do for this book, or was most of it based out of history you have already studied?

I am a historian by training and profession, often thinking and writing with Afghan history. In that sense, I am perpetually at research. But to paraphrase a dervish from one of Naguib Mahfouz’s stories, perhaps the aim of book learning is to suggest the limits of book learning. Nothing replaces experience and one must seek it where one can. Sometimes it can be a fleeting moment, as when you are struggling to communicate with an elderly Kurdish uncle on the tarmac in Gaziantep, trying to figure out how to travel together through the snowbound mountains on a night when neither of you are where you are supposed to be. Sometimes it lies in time stretched long, as when you watch the birds test the mulberry trees week after week from the windows of a quiet Tashkent flat, until the fruits are at last sweet enough.

For those who fall in love with this book, what other books or authors would you encourage them to read? (fiction, non-fiction, or both!)

Parwana Fayyaz’s poems in Forty Names, the stories of Rahnaward Zaryab (especially the novella Gulnar and the Mirror), and the stories of Abdul Wakil Sulamal. Novels might include The Devourers by Indra Das as well as The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar, The Longing of the Dervish by Hammour Ziada, The House of Rust by Khadija Abdalla Bajaber, The Widow’s Husband by Tamim Ansary, The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years by Shubnum Khan, and the novella The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn by Usman Malik. Also Usman Malik’s collection Midnight Doorways and the stories of Fatima Taqvi.

Can you tell us anything about stories you are working on now?

There are a couple of irons in the fire, let us see what comes of them. Beyond stories, I am concerned about storytelling itself. I have made noise wherever I can about the bloodthirsty orientalism of our narrative market in fantasy and science fiction; about how it does not mirror violence but curates it. This held true through decades of the so-called War on Terror and is still the case through Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza. We who take part in the narrative market must fight for a better one, a market that is a force for emancipation and justice. This is not only about the stories but their production and reception, exemplified in things like L.D. Lewis’s Watermelon Grant and Vajra Chandrasekera’s address upon winning the Le Guin Award. It is a long fight and our task is to wage it.

A silly question to finish up: You go to the store and come home with three things that weren’t on your list. What did you buy?

If I catch a whiff of qeema naan being freshly made and sold, I will trail off after it regardless of the plan. I am always on the lookout for an elegant notebook. If I come across a book that was printed in Afghanistan, I will buy it.

The Night Sweeps the Mountains Away is available for preorder here!

You can find more writing by Tanvir Ahmed at his author website!

Recent Comments